By Richard Heys

There has previously been much discussion including a recent ONS National Statistical blog by ONS DG Jonathan Athow about the inclusion of gold traded on the international markets – known as non-monetary gold – in the UK’s headline GDP and trade figures. Here Richard Heys writes about the work to reconsider how best to treat gold, and why adding the trade in crypto-currencies – such as bitcoin – into the figures may create further challenges.

Along with other national statistics institutes, the ONS[1] has invested significant time and effort into researching the modern economy and the digital revolution; how digitalisation has changed which goods and services are produced, how they are produced, and what prices are charged for them.

How then did we come to write a research paper focussed on a basic metal which has been mined for over 5,000 years and which would be instantly recognisable to ancient kings and pharaohs like Tutankhamun, Solomon and Midas? Why have we ended up thinking deep thoughts about a physical yellow metal which has lustre and does not corrode rather than intangible bits and bytes?

The answer is how statisticians think about assets and particularly how they sub-divide these into different groups: at the highest level we divide assets into financial and non-financial assets. Non-financial assets can be thought of as the machines, buildings and intangibles which go into productive activity. Financial assets conversely are traded on the market and give the holder a claim against some other entity – in the jargon a ‘corresponding liability’.

International work to update the rules which guide how countries compile their national accounts, has over the last few years been grappling with a problem: how to deal with a crypto-asset like Bitcoin which has no corresponding liability? In simple terms, Bitcoins don’t contribute directly to the production of other goods and services, so are hard to think about as a produced non-financial asset in the normal way but, by being without a corresponding liability, they don’t qualify as financial assets either.

The answer, which was initially mooted, was to place Bitcoin in a category called ‘valuables’. What is a ‘valuable’? Essentially, it’s a produced non-financial asset which isn’t used in the production process but is held by institutions as a store of wealth. Think fine wine and vintage cars, Picassos and diamonds.

Think Gold.

For most countries statistics show valuables as a very small part of its national accounts, both because these types of assets are generally held by a small fraction of society, but also because the key international markets in these assets are based in a small number of key locations, and when it comes to gold, no location is more important than the London Gold Exchange. The World Gold Council estimates approximately 70% of global gold trades still happen in the UK.

So why is that a problem? One can put Bitcoin together with gold into valuables and everything makes sense. Yes?

Unfortunately not. The problem is neither gold nor Bitcoin operate as a store of wealth in the normal ways. What is normal? Well, if one wanted to store value, one might want to choose an asset with a stable price which drifts upwards in line with the markets. One might expect this asset to be held by institutions which trade it infrequently and hold it for long periods of time.

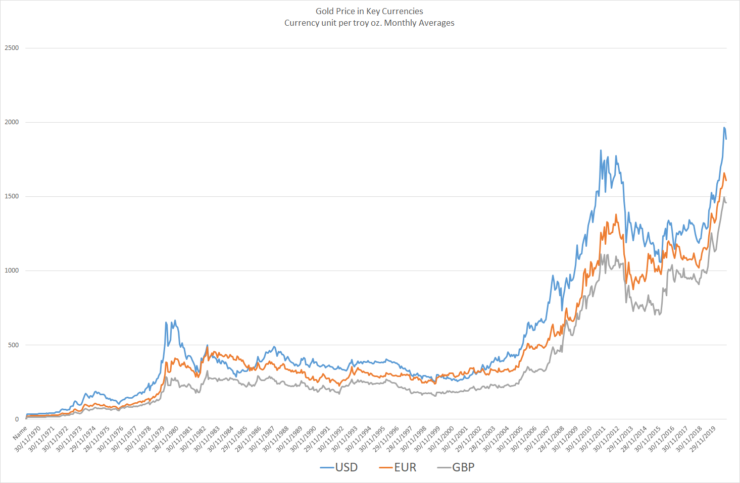

Most gold traded in the UK is held by large financial institutions – indeed almost no-one would consider it unusual to see some type of gold holding in a balanced investment portfolio. Used predominantly for speculation and hedging, the price of gold has been highly volatile in recent years (prices fell 25% in 2013-14) and has seen significant shifts in the volume of trading activity.

Gold prices (£sterling) (2010-2020)

Source: World Gold Council www.gold.org. Available monthly or daily https://www.gold.org/goldhub/data/gold-prices

Note: Pre 1999 Euro is represented by the Deutschemark path.

And that causes issues in how to present figures in ways which are meaningful to users. When valuables are traded there are two equal and opposite transactions: the change in the stock of valuables and a corresponding item in trade figures. In recent years gold trading has rapidly grown. This has caused measures of investment (known as gross capital formation) to move by up to 17% in a single quarter, and moved trade figures by an equal and opposite amount without any real change either in the degree of investment in British industry or a change in the volume of goods and services being traded. Adding Bitcoin, and other similar crypto-assets which are highly traded and also have highly variable prices, would exacerbate this issue.

Obviously from a UK perspective this would challenge the ONS to further refine its communication of increasingly complex data, but we know that Bitcoin mining and similar activity often happens in developing countries – the nightmare situation is a small nation’s statistical body trying to explain to a sceptical media or stock exchange why its trade balance has moved by 20% in response to a large price change in one or more crypto-assets.

The content of economic data may move markets, but national statistical institutes do all they can to not cause such shifts through the way they present these data. Putting volatile assets into parts of a nation’s figures that may cause confusion in the markets should clearly be avoided.

The proposal we suggest in our Discussion Paper is that maybe Bitcoin is a financial asset after all. And if that’s true for Bitcoin then its surely true for gold too. After all, if financial regulators, financial markets and tax authorities all treat gold as a financial asset it seems perverse for the economic statistics community to consider it differently just to maintain the purity of the concept that financial assets have to have a corresponding liability.

This category of valuables, which counts towards a country’s productive capital stock but doesn’t contribute towards production while containing assets which have many of the key characteristics of financial assets, is becoming an increasingly difficult accommodation to manage as these assets are increasingly traded as financial assets. Indeed, one could also argue that failing to recognise these as financial assets is distorting our view of these key markets.

Conceptual tidiness is important, but sometimes we all need to take a pragmatic approach and one solution may be to group assets which are primarily financial by nature into a revised financial assets definition. After all, there is one financial asset which currently doesn’t have a corresponding liability and sets a precedent, even under the current treatment. That’s right – gold held by monetary authorities as reserves.

[1] ESCoE Discussion Papers and related blogs describe research in progress by the author(s) and are published to elicit comments and to further debate. Any views expressed are solely those of the author(s) and so cannot be taken to represent those of the Office for National Statistics (ONS) or the Economic Statistics Centre of Excellence (ESCoE).

You can download and read a full copy of the Discussion Paper here.

Richard Heys is Deputy Director & Deputy Chief Economist at ONS.

ESCoE blogs are published to further debate. Any views expressed are solely those of the author(s) and so cannot be taken to represent those of the ESCoE, its partner institutions or the Office for National Statistics.