By Diane Coyle

Many cultural and heritage assets such as heritage sites, museum collections or archives are not recorded in national accounts, yet the capital services they provide can create economic value. In some ways cultural and heritage capital (CHC) resembles natural capital: parts of the services provided by the assets are recorded in current data, including, for example, commercial revenues from entry fees or cafes, but other parts are missing from the statistics. Is it possible to incorporate this ‘missing capital’, just as there has been progress in recording more of the economic services provided by nature, with the System of Environmental Economic Accounting (SEEA)?

In principle, yes: there is no reason why CHC assets not currently included in national accounts should be treated differently from other types of asset, which are increasingly being included in the national accounts framework. Similarly, CHC assets should be considered in the development of broader social welfare measures in the ‘Beyond GDP’ agenda. In practice, there are several hurdles.

One important question is how to value what are often, by definition, distinctive assets without an obvious market price. Yet to include CHC assets in the national accounts on the same basis as other assets, the valuation basis should be the exchange value, or in other words; either a market price or a method close to it such as replacement cost. This is the only approach consistent with the System of National Accounts (SNA) and the SEEA. Yet – just as with some natural assets – the notion of a replacement cost for the British Library’s collections or a painting in the Tate is not very meaningful. Even where there are some market prices, as for paintings, these are one-off prices that are hard to predict or compare.

While consistency with the approach taken in the national accounts requires the use of exchange values for cultural and heritage capital, measuring its social value – as part of inclusive wealth in the ‘Beyond GDP’ agenda – requires the use of accounting or shadow prices. In our new Discussion Paper we discuss the alternative approaches to valuing cultural and heritage capital, and the challenges involved.

However, there are other challenges to address too. One is simply classifying the types of assets and the services they provide. There are different potential classifications of each. For example, categories of asset could include heritage sites, archives and libraries, collections, arts, historic buildings – but some assets would span different categories (an archive in a listed building for example). Some would also overlap with natural capital, such as landscaped gardens and national parks. CHC assets also have distinctive aspects when it comes to thinking about how quickly they depreciate: for example, many 1960s buildings were not seen as a worthwhile part of heritage for some time after they were built but some are now highly valued in cultural terms.

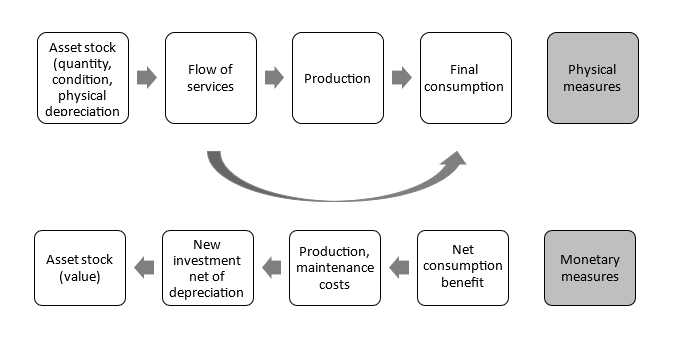

When it comes to classifying the economic services provided by CHC assets, we follow the same ‘production function’ approach as for considering any other asset (including natural capital) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Schematic of economic stock flow model

Source: Authors’ elaboration

The services can be divided into provisioning, regulating, supporting and cultural services – the same categories used in thinking about the services provided by natural capital. We suggest a classification, as a starting point for discussion.

Finally, a basic challenge is data collection. While there are some existing sources of data on our rich cultural heritage, incorporating CHC assets into either the national accounts or – with alternative valuation methods – a measure of inclusive wealth would require considerably more.

Yet there is self-evidently economic value in the nation’s wealth of cultural and heritage assets, alongside their important non-economic value. They support a creative industries sector accounting for 5-6% of UK GDP, and this is a focus of the UK Government’s creative growth strategy. The statistics that are captured – such as number of visits or tourism spending – amply show the importance of CHC assets to the economy, in addition to their huge aesthetic, cultural and historic value.

Read the full ESCoE Discussion Paper here.

ESCoE blogs are published to further debate. Any views expressed are solely those of the author(s) and so cannot be taken to represent those of the ESCoE, its partner institutions or the Office for National Statistics.